LONG RANGE STUDIO VISITS

Kinga Bartis and Mark Jackson

In the next conversation of our Long Range Studio Visits series we introduce Kinga Bartis and Mark Jackson. Both artists work with painting and drawing, and are interested in topics related to their personal experiences. In this article they talk about their routines of work during the pandemic, their inspirations and what being artists mean to them.

Kinga Bartis, The Only Way out is Through, oil on canvas, 150x100cm, 2019

Kinga Bartis is a Transylvanian-Hungarian born artist, currently living and working in Copenhagen. Her paintings are based on reflections of existence and similar matters in various power relations, navigating between the private and the political, depicting a mental landscape with a subjectivity that resonates between the inner universe and the outside world. She uses painting as a tool to disrupt socially constructed divisions, aiming to explore the possibilities beyond the so-called rational.

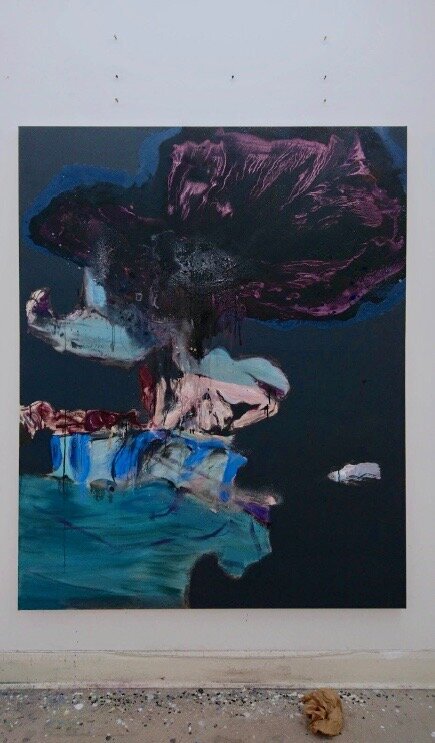

Mark Jackson, The Waves, oil, floor sweepings and washed up train ticket on canvas, 185 x 145cm, 2020

Mark Jackson lives and works in south London, he makes paintings of unreal, abstracted, figures and faces. Their embodiment in paint is their essence, made up as they are of spills, swirls of paint, veiled layers, illusory droplets of light and gestural abstract passages. Conjured using an array of techniques, in their undoing and their coming together, they are works that explore their own artificiality.

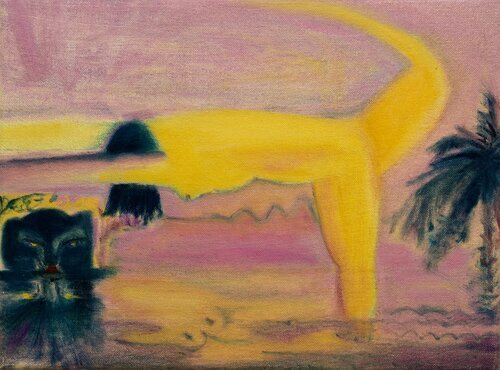

Kinga Bartis, Eternal Waters, oil on canvas, 30x40 cm, 2018

Mark Jackson: Hi Kinga, I’m just waiting for the sun to go down, so I can actually see my computer screen properly and then I’ll choose a few recent shots to share with you… I am enjoying looking through yours, I can see swimmers, figures reclining and kissing? Obviously we both paint swimmers occasionally!

Kinga Bartis: Hi Mark, I have been busy the last few weeks with a drawing project, I’m going to make a mural here in Copenhagen in May. So just been trying to find a fitting aesthetic. I have been looking at your work too, can you describe your studio practice and how it has changed since returning from PADA?

MJ: I like to start early. I’m up at 6.30 when the cat bites my feet, then all being well I can get to the studio for 9. And I’ll work until about 6. My work doesn’t have a definite process, so routines don’t work for me at the moment. I have tendencies - like, I work on lots of things at once. And for some reason I feel that from 11 until lunch and from 3 until 6 are my really productive hours.

When I went to PADA I was re-thinking my work. I’d previously made a really tight show of small oil paintings and knew I didn’t want to do that forever. So PADA was a great time to experiment with new imagery and approaches. I’ve since been able to hold on to the openness of my work at PADA, which takes a certain kind of discipline.

KB: Could you elaborate on that? Openness? You mean leaving it open instead of deciding what it should be about?

MJ: Kind of. I mean leaving the process open, so that deciding what the painting really is, evolves during its making. How about your studio routine?

KB: Arriving at noon, drinking coffee, and doing all the admin work until the afternoon walk (4ish), then getting into painting at the latest around 6. On days I don’t have to answer emails I just sit around looking at the canvas/es. For some reason I can’t really focus when the sun is up, but everything gets easier after sunset. Then the work begins. Before Corona times I could stay in the studio until 2 in the morning or so, but now I have to catch the last metro at midnight. What have you got in production now?

MJ: I’ve got some big canvases on the go and I’ve finished 5 of them. Some have taken 2 years to make, others only a month or so - it’s not dependent on their size. I’ve also got 5 or 6 big paintings on the go at the moment. They’re paintings of swimmers, divers, falling figures, figures dissolving into their landscapes. I’m also making works on paper - monotypes, oil on paper works and collages. And the collages are feeding into the large works - big sections of canvas cut and pasted. It’s all for an imaginary solo show. It’ll be ready in a few months!

Mark Jackson, mercury (shrouded, oil, pigments and pastel on linen on panel, 40 x 30cm, 2018

KB: I also made divers previously. I was very much into the free fall, mostly the feeling of it or the thought of actually jumping. It was very much a personal case and I really wanted to transform it into painting. The way you were describing it - to paint with it - I think it is very well put. When I painted those works I thought: ok, here it is, this is over (someone very close to me died), there is nothing here. Either I lose it or try to generate some kind of energy. The arriving part was not planned, I thought I am going to fall forever. Re the landscape part, it is important to put the figures into the world (landscape). That is how I resonate with it. There has to be ‘the world’ where the motives are a part of it, and the world has to also be in the motives, otherwise I wouldn't be able to relate to them.

MJ: I'm sorry to hear you lost someone close to you. I understand that impulse to work with free-falling figures that comes out of grieving. A friend said to me recently 'Is your work all about losing your Dad?' I was taken aback because I'd not thought about it like that - so directly, but they were right, to a degree. And your point about motives and the landscape is a good one. But there is something that interests me when the figure is in free fall - that it's not touching anything, and so is in some ways totally disconnected from the world - metaphorically speaking. I like this as an idea. The figure is out of touch - on its way out... Maybe I want my figures to be just about in touch, but grasping…

KB: How have you adapted your practice in the last weeks/months?

MJ: I’ve just had more time in the studio. I’ve been lucky. I saw it as a time to focus less on finishing paintings and more on experimentation. It’s been productive but the backdrop to this is so terrible for so many people, that it’s hard to enjoy studio time really. In fact I feel rather guilty about carrying on… but I do...

KB: How is your community responding?

MJ: Me and a few friends are sharing work via email and responding to each others’ progressions. Then there’s the Artist Support Pledge, initiated by Matthew Burroughs, which I think is a great thing to come out of this for less established artists. There’s a sense of interdependency and community that it builds that’s very encouraging. How is the situation in Copenhagen?

KB: Here in Denmark we have a functioning social welfare system and many people have a safe net to fall back to. Plus the government released helping packages to companies, even to artists. It’s all good, I would like to say though that I’m worried about the homeless, the socially fragile and all those whom we don’t really usually hear about. In the studio collective we closed the doors for visitors, and we cleaned more than usual. Some of us also agreed to come in in shifts, depending on their needs and health. We also discuss a lot about how we should manage things without crossing anyone’s limits. What will art be when we emerge from isolation?

MJ: Art will always be there for us. History changes art, but it doesn’t eradicate it. It’ll maybe take new forms, or have different content. Personally every time something life-changing happens, I grip to art more and more. It grows with you.Has your studio practice changed since returning from PADA?

Kinga Bartis, studio view

KB: During my stay in PADA I made some works that were shown in a prestigious exhibition here in DK. A lot has changed since that, which is really nice but there are now more demands on my attention and more work on my part. As for reading and writing, they are an essential part. With fiction I find inspiration in artistic expressions and universes, while non-fiction gives me tools on how to formulate myself in relation to my works, to put them in context and also to see things in a broader, more connected way. Recently I have been working on some drawings that will be shown in Sweden in a group show at the end of May, then I’ll make a mural in Copenhagen in mid May. The scale is huge, around 12 x13 m on a public hall, that accommodates sport events, bigger gatherings, concerts. It’s a project curated by Jens-Peter Brask, and he invited 8 artists to decorate the outside of the building. I am very excited about the task. Then hopefully a duo show with my friend Coline Marotta in June, which was postponed. We know each other from the Art Academy in Copenhagen where we both studied. We always had a lot of common elements in our practices, so it has been very interesting to work towards that show. We decided on a concept, then we worked for months and discussed a bit afterwards. We work both with the not-rational. I wouldn’t call it irrational, but maybe invisible, the not-formulated. I am interested in grasping what language can’t grasp any more, and I think painting is a great tool for that.

MJ: How have you adapted your practice in the last weeks/months?

KB: I’ve tried but I find it really difficult to focus. So usually I draw more and try to engage with the material through drawings. It helps me tune in and concentrate. I’ve also been reading more again. I try to approach it as transition time, remembering that things will settle at some point. It’s important to hit a mellow tune in my head otherwise things can feel really heavy. So books can help hitting that tune.

MJ: Is there anything you have learnt from this experience that you will carry forward?

KB: Generally I hope this pandemic highlighted the importance of reproductive work, how the labour of healthcare and social workers has been unrecognised despite societies- lives depend on it. And service workers for example: if metro stations, offices and public spaces wouldn’t be cleaned and “safe for work” we would not be able to full fill our tasks and do our “clean jobs”. That’s not so much about art though. But yes, hopefully artists can find interesting ways for evaluations and reflections. I really hope generally that people will do more for the community and for the socially less powerful and share their privilege instead of accumulating their wealth.

MJ: It’s good to get to know you a little bit from your answers! I’m interested in what you said about your projects and ‘grasping what language can’t grasp any more, and I think painting is a great tool for that.’ Well I very much agree with that. I think paintings are very mysterious by nature, they cannot be easily explained, they resist explanation even. This is what attracts us to them. They’re like invitations to get to know them, because they lure us in, but then they say ‘over to you’, ‘you decide what I mean!’

KB: Is that why you decided to become an artist?

MJ: I’m mesmerised by art. I probably didn’t choose it outright, but chose not to stop doing it. And I do it because I find it the most interesting, difficult and challenging way to get to know the world and other people. Also the potential for the experience of beauty and insight is great!

Mark Jackson, Field, oil on canvas, 240 x 150cm, 2020

KB: Do you have any thoughts about the artist’s responsibility towards the community, society?

MJ: I don’t believe artists are special. I think they are the same as everybody else and that everybody has a responsibility to society. So that is to be kind to people, one’s surroundings etc., be part of public life. Artists do however offer the community something different - their art. But I feel that artists shouldn’t be shackled by that as a responsibility in itself. I quite like that some of the American artists of the post-war era protested against the war in Vietnam, but kept their work on a different track - perhaps a formalist one. But both ways work for me…

KB: That is what I meant by the responsibility of the artist. I think artists usually have insight, reflection and other ways of going about life. I am just really annoyed by the stereotypes and prejudices people have about artists and usually they think we are some kind of magical weirdos living in solitude, making strange works, when actually an art practice is a lot of reflection, knowledge making and sharing, financial struggle and involvement with the world around us. And all I see is the opposite when it comes to politics and society and how people vote and relate to immigration, labour and values in general.

MJ: I don't think that it's just artists who have that insight - just certain types of people. Do you find that there are prejudices about artists where you live? I'm sure there are here too but I don't come across it much because pretty much most of my friends are artists or involved with the arts. And I work in the art world too. I agree it is a huge commitment - the financial struggle is hard, and there are many compromises we have to make in terms of free time. Regarding people's values I think that the majority of people act for the greater good when there is no scarcity of resources or fear. As soon as this happens - like now - there's a bit more of every-person-for-themselves - and then people vote selfishly. It's hard to take...

KB: Are there any personal elements in your works?

MJ: Yes, very much. Although it is not explicit. I try to work at the margins of my thoughts and feelings. That’s to say I’m working in the dark with my subject matter. It arises, and I paint with it, or against it. I’m an atheist and feel that’s very personal and plays a role in how the work turns out - but nobody else would know.

KB: That is very interesting, could you say a bit more about that?

MJ: Yes. It's that I've tried my hardest to paint what really matters to me. For me religion is a way to structure society, can provide an ethical anchor, can help communities and people in times of desperate need. But it obviously has its downsides too! Like many people, I don't feel I need religion in my life. But I do need some of those things that it can give. For me art plays a huge role here. Maybe how my atheism comes out in my work through a sense of inevitability about what we are as humans - at least that's how I think of them.

KB: How would you describe the aesthetics and content of your works?

MJ: Hmm that’s a tough one. They’re always tighter than I want them to be. I’d have to leave that one to others to describe I think. Off the top of my head I’d say, figures in a state of undoing, being absorbed by their landscape or the painterly ground. I try to occupy that busy place between abstraction and figuration. I do that because I find it the most giving kind of image-generation place. When you get it right the imagination fires up! And how do you make a painting - from scratch. Could you describe your process for me?

Kinga Bartis, Techno Tears, oil on canvas, 40x36, 2020

KB: I don’t have visions but I translate sensations and feelings, moods into images in my head. As long as I can remember I always tried to describe feelings with images - a body or bodies in a landscape to my parents as they had difficulties relating to the way I experienced life. So I still try to be as basic as possible with the motives, but more complex and ambiguous through the way of presenting them. I do a very small sketch, then this image usually generates a color palette, or sometimes I already have in mind, a color or a duo of colors. So the sketch is mostly about the composition of the colours and the motives.

But then just by switching to paint, a lot of the elements get altered, more open, organic and many transformations occur. I usually pay attention to what the material suggests, how the canvas is responding, how the colors are playing together and how they generate the shapes and forms on the painting. All this is open inside the concept. The concept I usually have beforehand. I don’t like the word concept, maybe framework or universe or a mental space. Change is very important. They all change and one painting generates the other. I used to think that my works were very static - maybe they still are. But the practice definitely has a movement. It is a bit like aging, you can’t see it from day to day but looking back you say, oh god, I changed since! I put some process photos to the folder to show how the painting changed through the making of that one called Techno Tears. What are your thoughts on your drawings and your oil paintings? What is your relation towards your monotypes and drawings and then painting?

MJ: There’s no progression really from one medium to the other. With my old work I used to basically arrange all of the elements in Photoshop - drawings and digital elements would be collaged together, then there’d be sometimes dozens of Photoshop layers of interventions before I’d settle on the image. Once I’d got my ‘finished painting’ on screen, I’d then translate it meticulously to a marble-smooth gesso panel, in oil paint. So basically I used to work in quite a systematic way.

But a couple of years ago I felt like improvisation in the painting medium itself was important, so I changed my work. Now there’s little hierarchy between small works on paper and 2 meter tall paintings. Sometimes I plan paintings a little on my phone, then I paint them, then I change them. But I try to improvise. What I gain from this is unexpected moments. There’s a sense of invention in the moment, and discovery. It also means that paintings fail. I’d say at the moment I have a 50/50 success rate. I abandoned ‘having a process’ as a definite way to make work a couple of years ago. Since then things are a bit more lively!

Something about monotypes and drawing. Things can happen quickly. There are impulses and accidents everywhere in them. And this is definitely fuel for experimentation on a larger surface. In that large dark painting below I laid it flat and poured on the paint to create that cloud above the figure. This came directly from doing ‘palette monotypes’, where I pull an image from the palette at the end of the day, just on a piece of paper. Oh, and find all of it very hard to do. Painting is the hardest for me, which is why I like it so much.

Mark Jackson, untitled painting in progress, 2020

KB: It seems that space and speed even colours differ according to which medium you work with. What are your thoughts about it?

MJ: Yes, you’re right. I’m trying to get slowly to a style I suppose, but I’m not rushing it. So there’s a lot of variation in my output. And I use a wide range of materials so qualities differ accordingly. At the moment in the studio I’ve got pencil drawings, crayon, oil on paper, monotypes, small oils on canvas, very large oils on canvas. I pour paint, throw it on, brush it, scrape it on / off. There are washes, glazes, very thick sections. I use car primer spray paint, dust and floor sweepings, collage, charcoal, everything!

KB: Would be great to visit your studio one day. Thanks Mark for the conversation!

MJ: Thank you, Kinga! Good luck with your projects.

For more information and to see more examples of work visit

Kinga Bartis and Mark Jackson