LONG RANGE STUDIO VISITS

ALIA HAMAOUI + LENNART DE NEEF

This conversation brings together two artists whose practice focuses on objects and their perception in society, through time and technology. They play, reconstruct and redefine objects' roles and historical narratives.

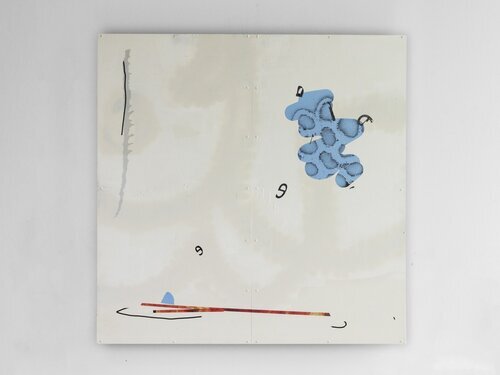

‘Building’ made by Lennart during his residency at PADA, shot by Martijn Lenten, February 2020

Lennart de Neef’s artistic research is mainly about the conflict between the virtually designed ‘hyperreality’ and the physical reality of these ideas. The majority of his works are considered as portals to a different dimension of this world, where things have been stripped of their original meaning, shaken (maybe broken), and put back on the canvas, open for re-interpretation.

‘Pro-Pylon’, foam and mesh and MDF, by Alia Hamaoui. Install shot from ‘Springboard’, September 2019

Alia Hamaoui’s multidisciplinary practice weaves together layered fragments, muted tones and lost histories. A combination of print, painting and construction; her work embodies a shift from physical remnants of the past to the digitizing of memories; explores how images, both printed and digitized, are intercepting our perspective on historical narratives and the exotic.

Lennart de Neef: Hi Alia! Nice to virtually meet you! It has been very interesting for me to dive into your world in this virtual way. In a weird way it really fits the subject of your work, but it’s really weird that I’m not able to see your works in real life now!

Alia Hamaoui: Hi Lennart, yes I definitely agree. I quite like how there is very much a possibility of us interpreting each other's work incorrectly due to the mediation through technology. Definitely a lot of mutual ground too. I thought first of asking you how you found PADA and the whole experience.

L: Before I went to PADA I had a very busy year building my studio and building up a network as a freelancer, but I was not working on my art practice a lot. So I thought of applying for residencies to give myself the time and focus to work on my art again, so I was very grateful to have this opportunity and it felt kind of unreal to be in a place surrounded only by artists, working on art and thinking about art all the time.

A: Yeah it seems like a luxury to just think about art and nothing else. Do you think it changed your work to be in this new environment?

L: I definitely think the new environment influenced what I made during my residency, but most important I finally had the time to materialise some ideas I was working on for a couple of years.

For example, after graduation I made a series of broken light boxes, which created the opportunity for me to show these kinds of objects and to be part of light festivals, but I felt like this was just a part of my artistic practice I was showing. PADA gave me the opportunity to work on other ideas and put them out in the world. That was for me the most valuable thing about the residency. How was PADA for you?

A: Yeah, I went this time last year. It was a residency run between PADA and Young Space. I graduated from art school the year before and I found it challenging to find out how to function in the new environment and to have the art school dialogue cut all of a sudden, so the idea of a residency really appealed to me. Overall it was a really good experience. In terms of making, I didn’t go there with a clear intention of what I wanted to make. But I think it was really important to step out of my normal studio environment and location, to not rely on my normal materials or everyday things.

Overview ‘Rise and Sign’ by Lennart at Dappie, Amsterdam, December 2017

L: I’m also curious about your practice now. After a year, are you still working on stuff that has been kickstarted at PADA?

A: I would probably say no. In September I got rid of my existing studio and we started building a new studio and gallery called Collective Ending, so I had to put my practice on hold for about 4 or 5 months.

L: Oh that sounds really nice, to be part of this community, could you tell a bit more about Collective Ending? What does this mean for you to be part of this?

A: Collective Ending is an artist-led initiative that tries to support emerging artists by providing them with projects to develop their practices in experimental settings. Part of this is a new studio and gallery we built, in a warehouse in a part of London called Deptford. We have now built studios to facilitate 9 practicing artists and 3 writers/curators/art historians. We also have a gallery space where we have been planning a series of shows to happen this year, but obviously this has all been put on hold. It’s been so amazing to have this support network and to have a sense of autonomy over something.

L: Being part of this collective and now being in a new environment with your studio, did this change your practice?

Install shot from ‘I Could Go On Forever’, PADA April 2019

A: Yeah definitely. I think more in the sense that it has opened me up so much more than just making objects or artworks in the studio. I have now been involved in organising shows and we are planning to do more live events. Being part of a collective not only gives you more of a strength through numbers but also just the ability to learn from each other. I was fed up with making works that felt like very ‘finalized’ ornate pieces. And I kind of wanted to make works that were a bit more an interaction and a play in between the objects, creating a sense of a world really.

So I am working more with found objects like take away boxes etc to integrate them more into the work, like you were saying in your statement: to investigate the boundaries between function and decoration and when something is an art object. It seems like a lot of things in your work also play with these ideas of the decorative and function and the art object, can you tell a bit more about this?

L: I think for me it’s very important to think about the attitude of an object. Because I’m educated as a designer, I’m trained to always think about what the purpose of the object is and how people will interact with it. You probably know the sentence ‘form follows function’, for me this is something I like to play with and to think about it in the opposite way. So when is the ‘form’, let’s say the decorative side of the object, more important than the function? Or can the ‘form’ be the function?

For me, making objects, I think a lot about these questions of form, functionality, being decorative and about the attitude of the object.

A: What do you mean by attitude? The personality of the object?

L: Well, an object can have a really functional attitude, but it’s also about the hierarchy. Between a pedestal and an art object for example; the pedestal serves the art object. But what happens if this is turned around and how to achieve this? I like to question this hierarchy and try to blur the boundaries of the attitude of these objects. For example the light boxes we were talking about earlier. Normally a light box serves a purpose; to show an image or message. I like to investigate what happens if you distort this image, does the object itself become more part of your experience and why is this happening?

Because of these questions I became fascinated with the idea of a movie set, where the objects are there just to represent a world or atmosphere. But what if the movie itself is about the set? What kind of set would this be? This set is what I am recently working on.

Work in progress, shot at Lennart’s studio, April 2020

A: I really like the idea of the hierarchy between objects. That’s something I think about quite often, so a lot of my works look like museum relics or artefacts. The relationship that the display has with the artefact. You know when you go into a museum and the artefacts are put on a specific type of plinth or have a specific type of image in the background and it’s that thing that kinda creates the story. I like to think how the images and the plinth as the ‘functional’ object are more successful in creating a story than the artefact itself.

L: Yeah I always think it’s very funny when people go to a historical museum and look at a plate from the Roman era which people just used as a plate and now is presented as this artefact behind glass. When did this plate shift from just a normal object, to this valuable piece of history?

A: Yeah I was listening to the radio the other day and the Museum of London put out an advert for people to send them objects that represent their experiences of quarantine. It is so weird, as we know this is going to be a moment in history and there is this premonition that this will be studied, it kind of collapses time down a bit and demonstrates this shift from everyday object to artefact.

L: Let’s talk more about artefacts. You create them from a future time in a way right? Can you tell me a bit more about why the artefact is such an important object in your work?

A: I am quite interested in our desire and relationship to disparate locations or moments in time that are separate from us, whether that is through time (the historical past) or geographically (the exotic). The artefact acts as a portal of connection between where we are now and the past. I am also quite interested in how false this experience is or how the story around the object is the connection and the object becomes a vessel for the story.

Susan Stewart wrote about the souvenir. Mass produced objects like the souvenirs are what we tend to have more of an intimate relationship with. For example if you have a souvenir of the Eiffel Tower on your bookcase it not only acts as a symbolic reference to the history of the object but it also reflects your personal experience of when you went to Paris.

Alia Hamaoui, ‘Do Touch’, soap, plastic tray and fringing. Install shot from ‘Absinthe’, February 2019

L: So it’s more about the story around it, or the memory it recalls?

A: Yeah definitely. But recently I have been bringing in the idea of the mass produced object a bit more. Making these things that feel they both have a sense of historical decay and fragmentation and also this reproduced sense. So they sit between this ambiguous state. On your website you have some projects, are they collaborative projects? Like the ‘On Show’, is this a collaborative project and do you work a lot in collaboration? Can you tell me more about that?

L: Yeah that was the first show I did after graduation. I felt the need to create a show together with 3 other recently graduated students about a subject we all were working on. And that’s why we made this exhibition. An exhibition about building up an exhibition.

A: So this echoes also your ideas about the movie set right?

Alia Hamaoui, current studio shot

L: Yes, but at this time I didn’t realise it yet. It was more about the question of when an exhibition starts to be an exhibition? Is it already an exhibition when you are building it? We changed the routing of the space. So you had to enter through the window in the back and experience the space backwards in a way. We also made some big white plinths on wheels. During the opening we invited people to sit on them, and to move them around the space. So the pedestals became art objects and were functioning as benches at the same time and were also redefining the space.

A: Well it definitely echoes the idea of objects sitting in between two realms. A bit like the non-places you told about in your statement, kind of like how things sit between two realms and it makes you question what purpose it is for and how objects have conflicting understandings if that makes sense?

L: Yeah for me it’s also a bit about the idea of identity. For example how the use of social media gives us all a very simple identity; just a bit of information, a few pictures and a few words.

A: Yes like everything has to be summarised, in as little words as possible and that closes down everything in a way.

L: Yes, and I think we as humans are so much more complex and nuanced than this summary. At these non-places, like on construction sites, I have the feeling that the objects can be free in a way - of their purpose and meaning. For me as a human I want to cherish this idea of freedom without trying to be a summarised version of myself. That feels very claustrophobic to me.

Lennart de Neef, overview of ‘On Show’ at the Academie Galerie, Utrecht , December 2016

A: Yeah, I agree on this. I am half Lebanese, half English and I grew up in Lebanon, then France, then England. So identifying with multiple places people always ask me ‘Where are you from?’ or want to know what place I identify myself with. But as a person you are a sum of all these things, so I can give them my full ten minute life history, which most people don’t want to hear, or I can narrow it down which doesn’t make sense.

L: It feels like it goes beyond the real connection you can have with a person if you want to connect with the few words somebody gives you as their identity. Like what happens for you as a person grown up from different places, that people want to know what culture it is you connect with. So they can relate to it, or not. And then this is what becomes their connection with you. Maybe we need to exercise this more with each other, to think less in these categories.

A: Yes, but I do think people by our nature, need to categorise things and break things down in a way. It is a comfort blanket being able to do so to understand this. But maybe you are right and we need to exercise this and be more transient and less prescriptive.

L: Yeah, and we should not forget that we live in a world that’s really complex. We have so much information and images to digest on a daily basis. So it is a very handy skill if you can categorise the world around you. Sometimes it feels like we are starting to behave like the technology we use, because that’s.. easy.

A: Becoming AI hybrids. But not only how machines are becoming more human, but humans being more like machines.

L: Well… Talking about that subject, I saw on your instagram that you posted the work of the American artist Tishan Hsu. I didn’t know his work, and I felt connected with it, so I started to read about him and he has been making works for decades already about the relation between the body and technology. So I was wondering what it is with his work that you are fascinated with.

A: I feel like he just blew everything open for me. Firstly at the time I was thinking about Minimalist sculpture and how his work alludes to this but also references technology and the body. He creates objects that have such an eerie presence of questioning the proximity we have to technology through this very penetrative language. Also, my work uses images and objects and thinks about the interplay of the two and I think he is someone who does this in a very successful way. Both in its material presence but using the image to create an illusionistic sensation.

Tishan Hsu at the Hammer Museum

L: Yeah and you work a lot with images in your work, right?

A: It is often how we experience the world. Often our first point of call is to google search something. I am also interested in the illusion or sense of a place and how we connect to it and images sit between being both present and physical and visual but there is a flatness to it. By combining the object and the image, the object gives a material and physical presence for the viewer, but the image is a suggestion of the lie or the falseness in our experiences. So I would say there is an honesty in images as it pretends to be nothing more than an image.

L: I think it’s interesting what you say about this honesty, because images can be manipulated very easily and they can be interpreted very differently by the viewer. Can you explain a bit what you mean with the honesty of an image?

A: Well, just in the sense that in an image in its nature is a representation of something. It cannot hide behind this. So even if the image is used to be deceitful or manipulated, I think this is more reflective of the user than the notion of the image. What about your relationship with images? On your website I saw some ‘paintings’ on which you worked a lot with fragmented images.

L: Well, those paintings I see as some kind of glitched version of reality. Like an image that went through a translation, but it was badly translated, so it became something different. For me this is again a way of investigating the meaning or purpose or identity of the image. And what happens if I take out just a few elements of the image - can it become a new thing and liberated from its original meaning? That’s an important process in my work which grew quite organically over the years.

Lennart de Neef, ‘Pond’ - 2019

So for example I bought this cutting plotter, a machine that can cut self-adhesive vinyl from vector images, to make my own stickers. And I photograph a lot of things I see on the streets, I translate these images through my computer to vector images and then cut them with this machine. In this process there is a lot of translation, first my view on the world, then the camera that translates to pixels, then my computer that translates these pixels to a vector file and then the machine that translates this data to a sticker, to material again. I am fascinated by this process, because it feels a bit like a metaphor for how we have to deal with all these images we see all the time and how we process them. I never see these paintings as finished objects, but more as studies. Most of these works are made in a timespan of 2 to 4 years.

A: That’s an interesting harmony, between you and the machine. How there are layers of distortion from the real situation. The machine dictates the work as much as you do in a sense. I mean obviously they have diagrams in them. But I definitely see them as diagrams of your ideas, less of them acting as paintings and more a mindmap, especially because they are quite minimal gestures, but it takes so long to happen. It’s really weird to talk about our works without the ability to see it in real life.

L: Yeah it feels weird to talk about these subjects of virtual stories and memory while not being able to physically relate to the artworks. Kind of a meta situation here. But without the whole situation of not being able to connect in real life now, this conversation probably would never have existed.

A: Yeah I wonder how this conversation would have been different if it had been in a physical setting…

For more information and to see more examples of work visit

Alia Hamaoui and Lennart de Neef